French author and diplomat Romain Gary wroteThe Roots of Heaven (Les Racines du Ciel) long before animal rights groups were blocking traffic in Beverly Hills.

Gary’s book merits being a cover-to-cover read in today’s multicultural fiction market because it was a game changer, ahead of its time, and because it offers a sense of place that goes beyond The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Hemingway’s tale of white dominated Africa.

Contemporary critics harbor a certain disdain forRoots of Heaven since Gary’s characters succeed at the politically incorrect task of romanticizing a colonial era most would like to forget. The culturally diverse characters are all misfits, acting out their life scripts in a thankless corner of the world.

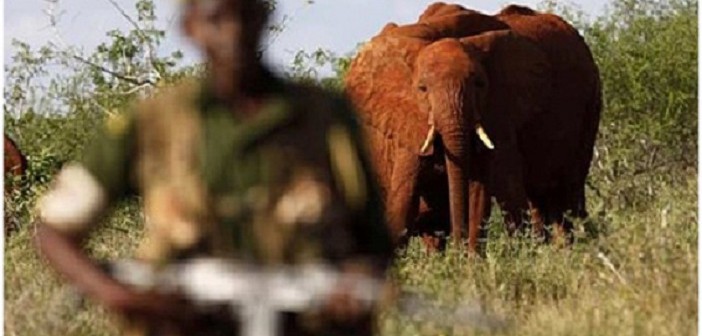

The anti-hero, Morel, is a French dentist with fatalistic personality traits. He is existential, a man who conducts his own guerrilla war against big money ivory hunters, elephant poachers and politicians in French Equatorial Africa during the groundswell of African nationalism.

He picks up support from a cast of characters who are running from the demons in their past. Forsythe, an ex-U.S. military officer who got caught up in a scandal during the Korean War and can’t go home again. Minna, a nightclub dancer who fled Nazi Germany, whose companionship enables Morel. Waitari, who was removed from the French National Assembly for his African Nationalist views and vacillates between anger and the melancholy that one still sees in nations where politicians still struggle with the psychopathology of post-colonial underdevelopment.

The death of Morel made the book resonate in the French psyche as it struggled traumatically with the fate of the African colonial empire after the fall of French Vietnam and the Algerian War. Among well regarded American Vietnam war novels, neither Phillip Caputo’s A Rumor of War nor Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers explored the American psyche in this way.

The backdrop for this soul searching is Fort Lamy, now N’Djamena, capital of Chad.

Les Racines du Ciel won the 1956 Prix Goncourt as France’s best novel. The book was translated into English as The Roots of Heaven in 1958, the same year 20th Century Fox released a film based on the book, directed by John Huston. The fact that Gary was Consul General of France in Los Angeles and knew everybody in Hollywood at the time enhanced his image as an international literary hero.

Reading The Roots of Heaven cover to cover in English or French isn’t easy, because the book is out of print, and it is pricey. It can be obtained through the used book vendors working with Amazon and other megasites for between $20 and $200, depending on whether it’s hard or soft cover and, of course, the condition.

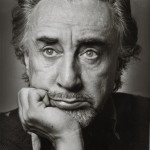

The big backstory of The Roots of Heaven is Romain Gary himself. Combat pilot. Free French Military Hero. Diplomat. Novelist. Film Director. Screenwriter. Playboy enough to rival Hugh Hefner.

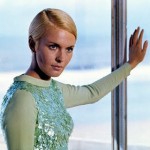

During the post-war period into the 1960s, neither the British nor the American cultural scene produced a literary figure as prolific, controversial, enigmatic and flamboyant as Romain Gary. His second marriage, to actress Jean Seberg, was icing on the cake. When he learned his wife was having an affair with a young actor named Clint Eastwood, Gary challenged him to a duel. Eastwood refused.

Gary has been called a literary con man by biographer David Bellos, and continues to be hated and vilified by French intellectuals, including some anti-semites, who have never considered him to be truly “French.” He put a gun to his head in Paris in 1980, a year after the troubled and controversial Seberg was found dead in her car. In a note “for the press” Gary said in no way was his decision to end his life related to her death.

It was revealed posthumously that Romain Gary fabricated the personality of Emile Ajar, who was credited with authoring La Vie Devant Soi, winner of the 1975 Prix Goncourt, making him the only person to have won the coveted literary award twice. This work first appeared in English in 1975, titled Momo, and in 1986 was retitled asThe Life Before Us. But the rules of the Goncourt Academy maintain that an individual can only win the prize once in a lifetime.

Romain Gary, one of France’s great modern writers, paid a high price for the thrill of beating the system. He remains a pariah in the literary world even today.