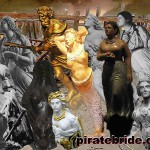

She’s not wooden and she can really see. All other figureheads on ships and boats—women, birds, serpents, centurions, and other creatures and things—are wooden and can’t see, although they were considered the “eyes” of the ship or boat when hung on the prow. They were also hung there to ward off evil spirits from the deep, and to “express the sailors’ belief that the ship was a living thing,” as the Royal Naval Museumdescribes another function of figureheads.

Simon Rose, writing for DarkRoastBlends, says, “In Germany, Belgium and Holland, it was believed that the ship’s figureheads contained spirits called Kaboutermannekes. These spirits protected the ship and crew from fierce storms, treacherous winds, uncharted rocks, illness or disease, and in the event the ship sank, the spirits would guide the sailors’ souls to the afterlife. If sailors lost their lives at sea without such protection, it was believed their souls would haunt the sea for all eternity.”

Figureheads, like those seen in the gallery below, became popular in the 16th Century when wooden galleons (large three-masts, square-rigged ships) were built with stem-heads (the top or forward most part of a ship’s stem), a place where the figureheads could be hung. (Click on any image and the gallery becomes a slideshow where you can control the change of images.)

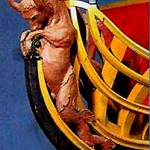

Charles Laurier Dufour has a different idea. As photographed here, the figurehead model, G, is on the port side of a tugboat—the workhorse of the harbor that pushes big ships around. Neither the tugboat nor model venture out to sea, and there are no monsters of the deep to ward off, but G is keeping a watchful eye on the shore. (We’ve seen her before on these pages.)

Charlie’s model G is not the scantily-clad witch Nannie in Robert Burns’ famous poem, Tam O’Shanter. Poor lad, he was chased by her after an all-night drink. Nannie is “dressed” only in a cutty sark, an archaic Scottish name for a short nightdress. Then all hell breaks loose in the poem.

Tam tint his reason a’ thegither,

And roars out, “Weel don, Cutty-sark!”

And in an instant all was dark:

And scarcely had Maggie [his horse]rallied,

When out the hellish legion sallied.

Charlie has made it much easier for us to “see” and “read.” Here the figurehead is stripped of all pretenses.

And, yes, the famous ship and the whisky, both Cutty Sarks, share the same poem. The figurehead on the Cutty Sark, pictured below in photo gallery, is the imagined Nannie in Burns’ poem. Who knew?!

(Charlie says: the only reason his model is on the side of the boat “…is about my composition. If there had been a way to safely shoot her on the front and still have a great composition, I would have just as easily done that.”)

Again, from the Royal Naval Museum: “The ancient Egyptians used figureheads to provide both protection and vision, by mounting figures of holy birds on the prows. Phoenicians used the heads of horses to symbolize vision and swiftness. The ancient Greeks had a boars’ head to represent vision and ferocity. Roman ships often carried a carving of a centurion to signify their elite fighting ability.

“In northern Europe, the favorite decoration for the long-ship was a serpent, although some Danish ships had dolphins, bulls or dragons. All were meant to strike fear into the enemy and scare away their enemy’s guardian spirits. By the 13th century, one of the favorite figureheads was the swan, renowned for its grace and mobility on the water.”

To the ordinary seaman, the figurehead symbolized his ship. I’m a land guy, so I’m stickin’ with Charlie, G and the tugboat, with an eye on the shore.