Five years before the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his legendary “I Have a Dream” speech that inspired millions of African-Americans during the final days of President John F. Kennedy’s “New Frontier”, Althea Gibson had a reality. She was the top-ranked female tennis player in the world and owned two Wimbledon titles. But more often than not she didn’t do her breakfasts at Wimbledon at the same places the rich white folks did.

After Althea retired, Maria Bueno of Brazil became the queen of Wimbledon and the number one ranked woman in the world. One can only wonder how the tennis world would have reacted to Althea if she was a Brazilian, where race and culture operate on a more socially inclusive model. Or if Bueno, whose skin color resembles African-American Hollywood stars Dorothy Dandridge and Lena Horne, might have faced the same obstacles Gibson encountered if she had launched her career in the United States.

Althea was born in Silver, South Carolina in 1927 and, like many African-Americans, her family moved to New York when she was a child, drawn by higher wage jobs and the cultural lure of the Harlem Renaissance.

Nearly six feet tall as a young teen, Althea showed athletic ability and drew the attention of Dr. Walter Johnson, a Lynchburg, Virginia, doctor who was active promoting tennis nationally among the nation’s African-American youth. His social network enabled Althea to cross over to the United States Tennis Association, which, in spite of incipient racism, accommodated her and gave her a platform to hone her amateur game. Johnson would also go on to mentor male black tennis legend Arthur Ashe.

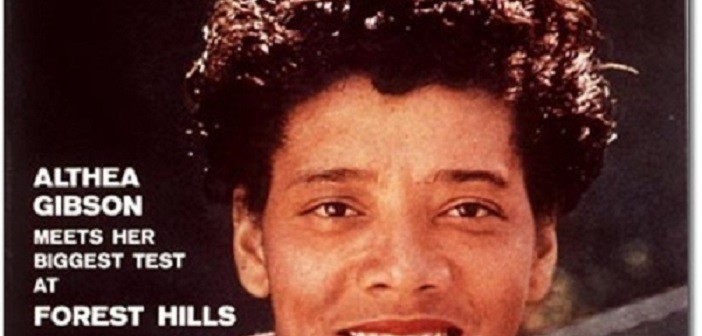

Graduating from all black Florida A&M University in 1953, Althea was already in the top 10 USTA rankings. In aYouTube interview she says she focused on playing winning tennis so much that the issue of racism stayed in the background. She also claimed that during her most successful years she was anti-social, not the prescription for success used by Serena and Venus Williams, that’s for sure.

She was the first African-American to be named female athlete of the year by the Associated Press in 1957. Since Wimbledon and the other Grand Slam tennis events were considered amateur sports and did not offer prize money, she retired at the top of her game after her 1958 victories at Wimbledon and the U.S. Open and did exhibitions, still facing segregation.

In an effort to monetize her star value, she earned $100,000, the amount that made Jim Brown the highest paid athlete in professional football, doing tennis exhibitions touring with the Harlem Globetrotters, a move thought by some on the more militant side of the black sports movement as being “Jim Crow.”

Life did not offer the center court celebrity she would have received had she played today. She embarked on a professional golf career without much success, age being a factor. She did a stint as New Jersey Commissioner for Sports during the late 1970s.

Two difficult marriages left psychological scars. By the early 1990s, Althea Gibson was down on her luck, in ill health and living on public assistance in New Jersey.

She continued to stay in touch with her old Wimbledon and French Open doubles partner, Angela Buxton. A former English star, Buxton, who is a Jew, also experienced discrimination during her tennis career. She called Buxton and said she was contemplating suicide.

Without telling Althea, Buxton arranged for a notice about the great champion to be published in a major tennis publication. Althea received contributions of more than a million dollars. She died of complications related to cancer in 2003.

Her favorite saying, which can be found on a plaque at Walt Disney’s The American Adventure at Epcot Center in Florida, is “no matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helps you.”