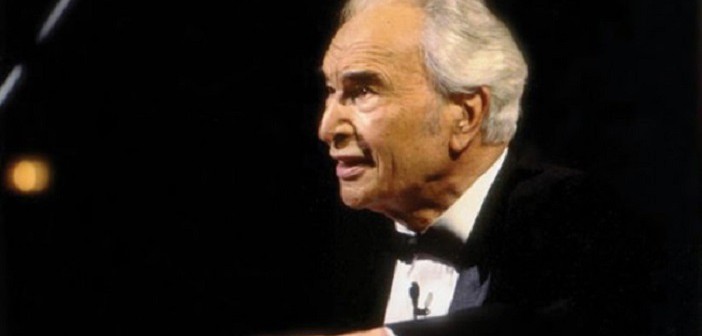

Like most young teens who grew up in America’s rock and roll capital, I had my share of Chuck Berry, Elvis and early Motown. But when my parents took me downtown to see The Dave Brubeck Quartet perform as part of the Cleveland Orchestra’s Summer Pops Concert series at Public Hall back in 1962, I already knew he was more than a jazz legend.

Brubeck’s Take Five had crossed over into the Billboard Hot 100 in 1961, becoming the first jazz instrumental to sell a million records. And his refusal to play venues that wouldn’t tolerate integrated groups like his, which featured African-American bass man Gene Wright, made news in Cleveland and other cities that were torn by racial strife.

When a major TV network agreed to broadcast a show featuring the integrated quartet but instructed the camermen to cut Wright out of the frame Brubeck made headlines by cancelling the date.

To keep TV moguls from cutting Wright out of the picture the group lined up with the bass man nestled right up alongside drummer Joe Morello and Desmond on the lonely side of the long grand piano.

Brubeck came from a good family in Concord, California, just north of Berkeley. He grew up in the days before there was a bridge linking the East Bay with San Francisco. His father was a rancher and his mother taught classical piano. He started studying to be a veteranarian at the College of the Pacific in Stockton, but his professors noted that his aptitude was more tuned in to music. Brubeck struggled with sightreading but developed his talent as a composer using counterpoint and creative tempos. He graduated in 1942 and was drafted into the U.S. Army.

Serving Uncle Sam he formed one of the Army’s first racially integrated bands and met fellow GI Paul Desmond, who played alto sax. The two developed a musical relationship that lasted a lifetime, spawning the genre known as contemporary jazz.

Brubeck also was a soldier in General George Patton’s Third Army in its operations prior to the Battle of the Bulge. The brutality and war crimes he witnessed helping to defeat Hitler’s quest for a Thousand Year Reich drove his commitment to make music that promoted peace and understanding.

You can read dozens of obituaries praising his musical accomplishments, but Dave Brubeck the man, was a cultural diplomat who was all about freedom.

It’s not surprising that Brubeck was presented a “Benjamin Franklin Award for Public Diplomacy” in 2008 by Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice for offering an American “vision of hope, opportunity and freedom through music.”

That music, from a former Third Army soldier, gives you a rather different feeling than what you get after watching Francis Ford Coppola’s “Patton.”

Time to Take Five for Dave. He left the house on December 6th. But like other old soldiers, his music won’t fade away.