Running the timeline of storytelling, it’s fair to say that American fiction writing owes much to the literary traditions of Britain and Ireland. But somewhere between Vietnam, Haight-Ashbury and Watergate, the globalization of culture jacked the mojo of the Hemingways, Faulkners and Fitzgeralds.

Today’s doyen of world fiction, Ian McEwan, operates in a literary marketplace that has less to do with his native England than with values and characters engineered by the same transatlantic consortium that enables Anglo-American culture to dominate the world stage.

McEwan’s creativity was not processed through the Iowa Writers Workshop, or nurtured by aYaddo grant or Gordon Lish, the former Esquireeditor known as “Captain Fiction” who spawned Phillip Roth, Bruce Jay Friedman and Ken Kesey.

While Richard Nixon was putting American novelists on his “enemies list,” Ian McEwan was finishing his education on the other side of the Atlantic.

The redbrick-educated McEwan broke into the stuffed shirt world of British publishing as an early product of Sir Malcolm Bradbury’s pioneering creative writing course at the University of East Anglia. A departure from the rigors of traditional English writer training, Bradbury mixed his passion for the Great American novel with American studies pedagogy and other ideas he gleaned from his time at the University of Indiana.

The diplomats, editors and sundry culture vultures McEwan penned into his 1998 Booker Prize winner Amsterdam—a tale of smarmy shape shifters, supernaturalism and deceit—should be considered a testimonial to his teacher as much as to him. Neither a man’s novel nor popular fiction,Amsterdam’s characters are of the ilk that expressed ambivalence to the lessers of society and the gutting of Britain’s social contract democracy during the transformational Labour government of Tony Blair.

Former British foreign secretary Douglas Hurd, chairman of the Booker selection committee, called Amsterdam “a sardonic and wise examination of the morals and culture of our time.” [See Editor’s Note at the end of this post.]

The retro dimension of class conflict one finds in Amsterdam and some of McEwan’s other works matches up with what American fiction produced during the late 19th century when Victorian literary tastes were generally dismissive of such themes.

When America was settling its accounts after the Civil War, William Dean Howells wrote his classic The Rise of Silas Lapham, an early American social novel driven by the conflicts between characters born into old money roiled by the nouveau riche. The Beacon Hill Brahmins provided a mirror culture of the London elites of the time. InAmsterdam, McEwan riffs on this same theme with the setting being a globalized English culture a century later.

With fiction writing at loggerheads with flat earth syndrome, and social tools like Twitter promoting groupthink, truncated attention spans, and, sadly, functional illiteracy, McEwan is a top influencer in the world of literature without the bombast of a Hemingway or a Norman Mailer. His passion for the writer’s craft is best evidenced by his being prolific and opening his tool box to shift genres.

By contrast, Jonathan Franzen, America’s top gun fiction writer, has produced only two books over the past decade. McEwan produced five, and participated in three screen adaptations of his work. Particular people can congregate over a glass and mull over what happened to the Great American Novel. Like good whisky, it requires hard work. Ian McEwan and Sir Malcolm might drink to that.

The Plotline

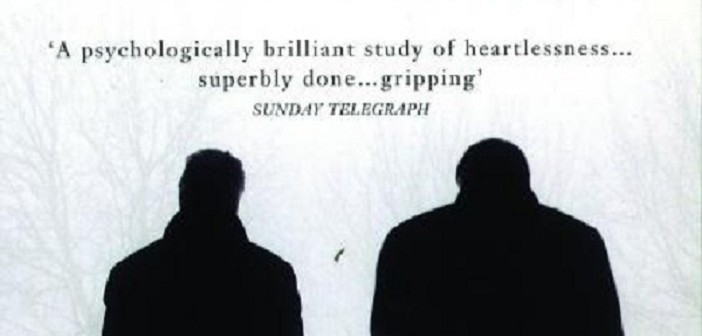

Set in contemporary England, the story revolves around two old friends, Clive, a prominent composer and Vernon, the editor of a leading political newspaper. Both men shared a girlfriend, Molly, in their youth and the plot unfolds as they attend her funeral. She died a painful death after a long, undisclosed illness. As if they were the administrators of each other’s living wills, the two make a euthanasia pact to avoid dying like Molly. The plot thickens as politics and mendacity impact the lives of both men, and intensifies when another of Molly’s former lovers, politician and prime minister hopeful Julian Carmony, stirs the cauldron. McEwan reminds readers why he got the nickname “Ian Macabre” as things spin out of control in Amsterdam, where euthanasia is legal.

By Eric Ehrmann

Editor’s Note: This is our first Must Read book for men. It’s first, conveniently, because the title begins with the letter A. It’s clearly a guy book. There will be others to follow, and we will compile these posts and your comments into a reader-driven referendum of the Top 10 and then maybe the Top 25 Must Reads for Men. Books, like whisky, women and song throughout these pages, are not easy things for us to agree about. Here for example, is Sam Jordison’s take on Amsterdam, writing for the Guardian. He calls it McEwan’s “worst novel” and he writes an interesting piece about how it could possibly have won the Booker prize for fiction. Where do you come out onAmsterdam?