Editor’s Note: At a time when most photographs are photoshopped, these are not. Read how Anthony Browell achieved this effect with a camera and a mirror, plus his skill in the darkroom.

As a boy in the 1960s I raced a tiny single sail dinghy on Sydney Harbour. The competition was cutthroat, but the real excitement came when a giant tanker cleaved a path through our bobbing fleet, scattering us like butterflies in its rolling bow wave. Back then Sydney was a busy international port with heavy harbour traffic and a well-established maritime infrastructure occupying the waterfront on either side of the Harbour Bridge.

Sadly it couldn’t last. In today’s Sydney, the soaring price of real estate, rampant developers and the inner city’s changing demographic has wrought enormous change to the working harbour I knew as a child. The slim wooden finger wharves of Woolloomooloo and Walsh Bay where bales of Australia’s finest merino were loaded onto elegant sailing clippers for the 60-day journey to the ‘Old’ Country now house the city’s rich and famous. Glass-encased apartments with monstrous powerboats lolling insolently at their doors line the docks where troop ships departed for two World Wars. Darling Harbour, once the site of shunting freight trains and towering cranes, is now a convention precinct, and already sadly down at heel. The families of bankers, lawyers and admen have renovated the wharfies’ cottages that line the narrow streets running down to the harbour. Multi-story apartment blocks stand on cleared industrial land. And surely in the ultimate irony “The Hungry Mile”, a prime strip of dockland named for the thousands of unemployed who lined up in vain for stevedoring work during the Great Depression, is currently slated for a Casino development.

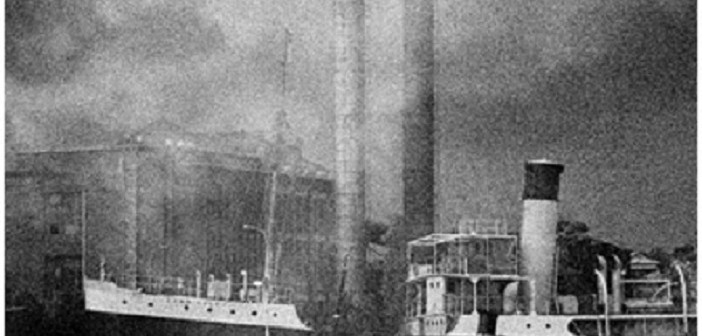

My friend Anthony Browell, one of Sydney’s finest photographers, had been watching Sydney’s great maritime heritage disappear literally before his eyes. Stirred into action, he began capturing images of the crumbling industrial edifices around his house in the waterfront suburb of Balmain. Anthony has a marine soul. At various times he has owned and skippered tug boats, fishing trawlers and even a paddle steamer. His other passion is architecture where his photography for Australia’s Pritzker-awarded architect Glen Murcutt has been internationally acclaimed. His eye for the built form and his empathy for the working harbour are clearly evident in this exceptional series of prints first exhibited at the Josef Lebovic Gallery in Sydney.

In his words the pictures are ‘embellished’ (shot through glass) to overlay the reflection of images such as clouds that are, in fact, behind the camera. He is not seeking just to document, but, through his choice and cropping of images, to interpret a sense of place that will soon be lost forever. It is this feeling for his subject and its imminent demise that he eloquently expressed in the notes to his Exhibition:

“Sydney’s Harbour is easily acknowledged as its heart and its prize. But a vital part of it, the old working waterfront, is much undervalued and rapidly disappearing. The semi-redundant industrial areas west of the Harbour Bridge, particularly – around Pyrmont, White Bay, and the remains of the old naval dockyard on Cockatoo Island – are extraordinary testimony to our recent past. But we can’t get rid of them fast enough.

Great tracts of this waterfront are being swept away annually in the name of residential development. These were extraordinary places, where mountains of coal were converted to electrical power in vast and ever-expanding corrugated cathedrals, and where that power was applied to the heavy engineering trades. It was a world of belching smoke, soot and stench, of steam railways, iron ships, and continuous wharves.

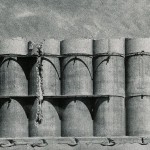

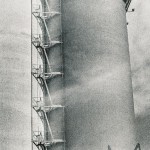

These surreal landscapes, which were built, rather than designed, evolved over decades of adaptation and modernization into an environment of massive contraptions of stunning variety. For me they are places of unexpected adventure, and these photographs represent the beginning of an attempt to document and interpret this disappearing industrial fairyland.

The few buildings that remain – silos, cranes, chimneys and sheds – are massive, purposeful. They demand respect. Very few were finessed in any way, because when these grand visions came to be they were beyond the design regulations and aesthetic considerations that applied to civic and domestic buildings. There was a kind of open slather attitude to waterside constructions. They were weird, big, brutal and crude, and these are the qualities I’ve used in these photographs – to emphasize the oddity, and the oversized strangeness, of an environment that will soon be no more.”